If you work in the education sector, you will be well aware of the importance of China. The country has provided a steady flow of qualified, capable students to universities, language schools, K-12 schools, and other kinds of institutions around the world for many years.

However, as the global market continues to evolve, China’s educational and digital landscape and the tactics required to achieve continuing success there are also changing.

Schools must remain current with the latest trends and happenings in China’s unique online ecosystem, economic factors that might influence student decision-making, and international policies and developments that might affect the flow of Chinese applicants.

Can schools look forward to more or less recruitment opportunities in China in the coming years? What does the current playing field of the Chinese internet look like? And how can schools gain more visibility online? Keep reading to learn more about the changing face of digital student recruitment in China.

The Current Digital Marketing Landscape in China

The launch of the Golden Shield Project – commonly known as The Great Firewall of China – in 2009 saw the banning of many popular global websites and apps and a resulting period of flux for the Chinese internet as domestic alternatives attempted to fill the gap.

Because the new market was somewhat less mature than the global environment, it underwent much more change in the ensuing years. Sites like the early Chinese social network RenRen became popular, only to be quickly replaced by superior competitors and all but disappear.

In the past few years, however, stability has emerged in the Chinese market, with the country’s biggest online players—Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu, and Sina—often referred to as ‘BATS’—consolidating their market power. This newfound stability makes it somewhat easier for schools to approach international student recruitment in China with a clearer idea of which channels and sites will drive growth.

Baidu still leads the search, with over 68% of the overall market, although alternatives such as Qihoo 360 Search and Sougou offer advantages. The latter, in particular, is the only search engine that can show results from Tencent’s social media app, WeChat. Schools looking to improve their results in Chinese organic search should prioritize developing Chinese language content, localizing their web hosting and domain name, and creating a simple, easy-to-follow architecture for easier SEO indexing.

Here Are Examples

Example: A typical Baidu search results page. The site’s format is reassuringly similar to Google.

In paid advertising, one area that has shown immense growth is mobile news feed ads. Offered by various platforms, this format has become increasingly preferred by brands and consumers as a non-intrusive form of online promotion. A recent report from iResearch predicts that ad spend in this area will grow by over fifty percent in the next year alone:

Baidu, in particular, has seen massive success with news feed ads, which have helped drive huge profit growth over the past year. AI drives Baidu’s personalized news feed app ads to target interested users better. Tencent-owned social apps like WeChat and QQ also offer their versions of news feed ads, while another player to watch out for is Toutiao. This news aggregation app boasts over 100 million daily users.

Example: An illustration of different news feed ads in Toutiao. Note how the ads blend quite seamlessly into other results.

Social media marketing in China, at least in the wealthier regions, is now very much dominated by two sites: Sina Weibo and WeChat. The former is similar to Twitter, offering a microblogging platform that allows users to create short text posts, photos, and videos and follow others to keep track of the latest trends.

Weibo has long been among the most receptive Chinese sites to content from Western brands and is a favorite for many schools looking to recruit students from China. The site also has a fairly advanced advertising platform with numerous formatting and targeting options.

Example: The Weibo homepage of the University of New South Wales.

However, there are signs that Weibo’s popularity is dwindling, with Toutiao hemorrhaging some of its market shares, so much so that the former accused the latter of illegally copying its content last year.

On the other hand, WeChat is going from strength to strength. Encompassing instant messaging, social networking, e-commerce, and even gaming and online dating into a single platform, it is more of a suite of different apps than a single one.

The platform’s incredible functionality has seen it amass over 980 million monthly active users, eclipsing the country’s former most popular social and messaging platform, QQ – a Tencent app and essentially an older, less sophisticated version of WeChat. However, it still has over 800 million monthly active users.

Schools can effectively leverage WeChat for student recruitment in many ways. The app offers a comprehensive ads suite, a social media feed known as WeChat Moments, and numerous features within its IM platform that can be used to engage students.

This includes several automated tools, such as customized link menus and auto-reply options.

Example: Dorset College integrates a customized menu for prospective Chinese students on its WeChat IM screen. The buttons at the bottom offer an introduction, campus information, and a Q&A. Depending on their click, Automated messages are sent to users.

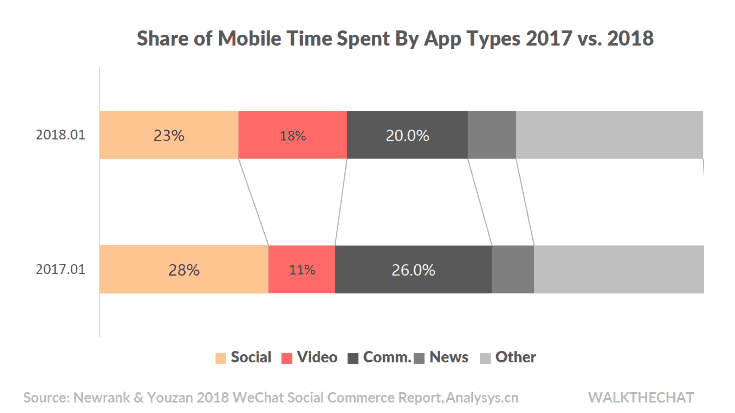

One area of the Chinese internet that schools may find becoming more important is video. Over the past couple of years, online video consumption has grown significantly in the country, with a recent WeChat Social Commerce Report released by Youzan and Newrank showing that it now accounts for 18% of total mobile browsing time, an increase of 7% of the previous year:

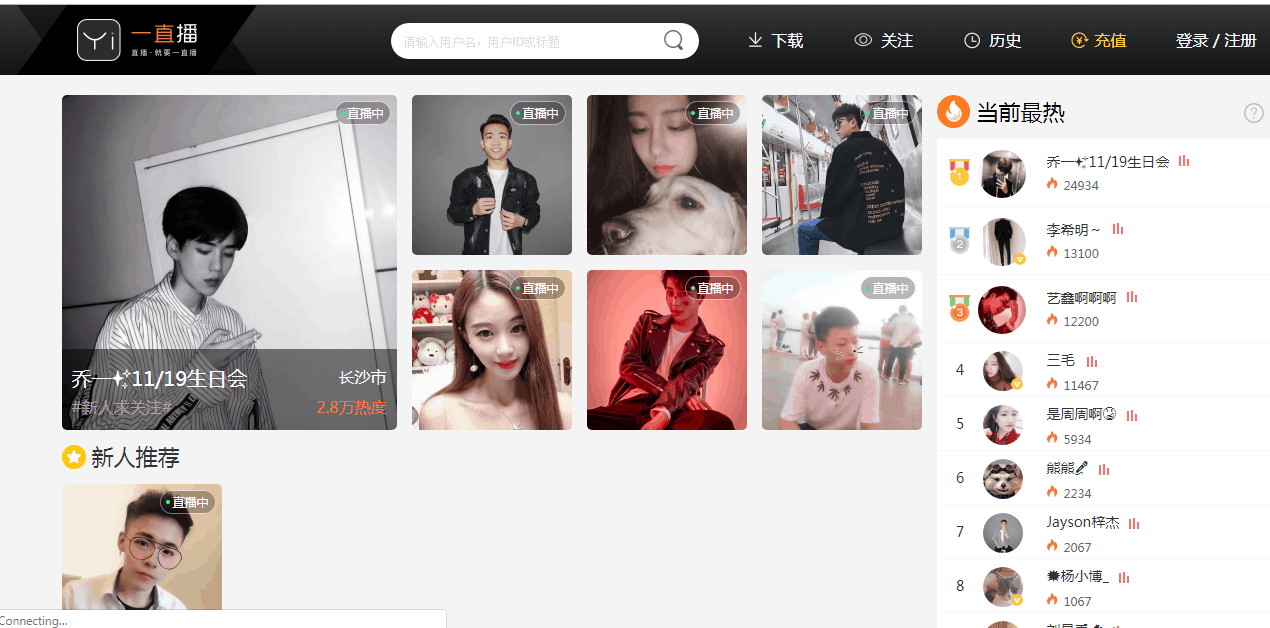

China’s most popular video sites include Youku, a hybrid of YouTube and Netflix offering user-generated and premium-licensed content. The site has over 580 million users. It may also be worth watching several sites that share micro videos and live-streaming content, such as Meipei, Miaopai, Yizhibo, and Kuaishou.

Example: The homepage of the livestreaming site Yizhibo.

As time passes, these smaller sites may threaten the dominance of larger, more established platforms. While they do not currently offer much in the way of student recruitment opportunities, this may well change as the sites mature. Conversely, their popularity may lead the likes of WeChat to focus more on live streaming and video—much as Facebook and Instagram did to ward off the threat of Snapchat—to consolidate their position.

Opportunities and Challenges in Chinese Student Recruitment

While international student mobility from China continues to grow fairly steadily year over year in most markets, many in the education sector are rightly concerned about the prospect of it finally reaching its peak and declining in the coming years.

Such is the importance of the Chinese student recruitment market and its exponential growth, and this scenario could have huge consequences for institutions that have come to rely heavily on the country to meet enrollment targets.

Indeed, World Bank data cited in a Universities UK report last year shows that the college-aged population of China will decline significantly by 2025:

Coupled with increasing numbers of schools making inroads into the Chinese market, institutions of all kinds could face a future with far more competition for fewer students.

However, there is a chance that this decline will be offset by another major shift in the market conditions: the growth of the Chinese middle class. In the past, most Chinese students studying overseas came from wealthier and upper-class families, as they were the only ones with sufficient resources.

As the middle class has grown, international education has become a far more obtainable reality for those outside the elite. With the rising cost of domestic education in China, international study is more accessible and attractive for this demographic.

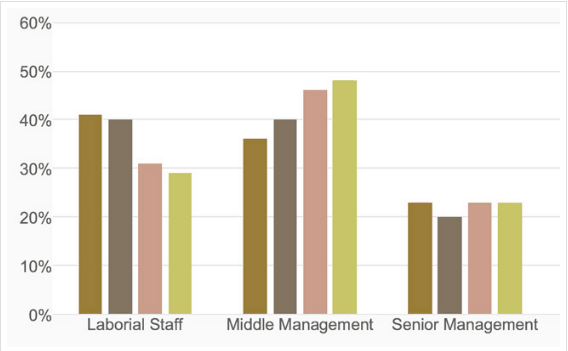

At the ICEF Beijing Workshop in 2017, Beijing Overseas Study Service Association (BOSSA) Director Peng Sang detailed the increase in students from families outside the traditional Chinese upper class seeking education abroad:

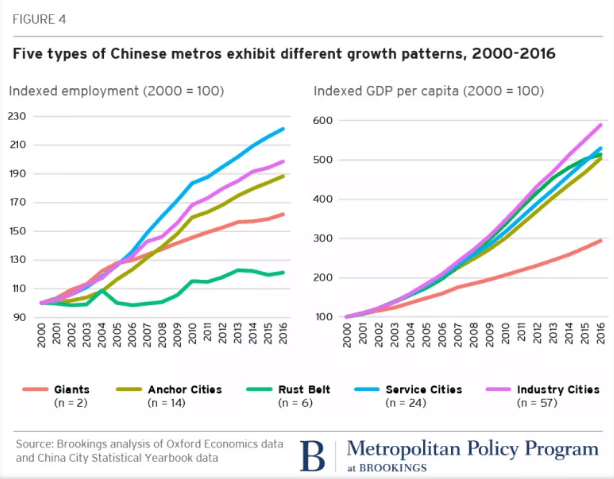

On a more macro level, China’s incredibly rapid urbanization may also contribute to increased demand in the future. The Brookings Institution’s 2018 Global Metro Monitor report, which tracks the growth of urban centres, found that 103 of the world’s largest metropolitan economies were now in China.

In 2014, there were fewer than 50. Growth in per capita GDP in these cities was also significantly higher than global averages:

Source: The Brookings Institution

This has also contributed to economic growth and migration shifting away from the country’s two largest cities, Beijing and Shanghai, which Brookings classified as its two ‘Giants,’ towards other cities, which it categorizes as “Anchor,’ ‘Service,’ ‘Rust Belt,’ or ‘Industry,’ depending on the city’s primary economic drivers.

Brookings mentions cities with prospering tech sectors poised to benefit from the changing landscape. These include Hangzhou, where internet giant Alibaba is headquartered, and Shenzhen, which is home to Tencent and Huawei, among other companies, and has been dubbed ‘the Silicon Valley of China.’

Further, schools could look to Brookings classifications as a starting point to identify some opportunities available to them should they target lower-tier cities. As an illustration, this handy chart from Business West offers an overview of 8-second tier cities and the main sectors with high business growth potential:

While this information is targeted towards organizations interested in exporting, schools who offer programs related to these fields could find targeting these cities very fruitful, as the growing urban population in these areas seeks the skills they need to survive in these new economies.

Chinese Students are Seeking Out a More Diverse Range of Study Destinations

Another point that BOSSA’s Peng Sang raised during the aforementioned ICEF Workshop was the increased diversification of preferred study destinations among Chinese students. He pointed to growth in Asia, particularly Japan, where enrollment of Chinese students has increased by 12% over the past year. Destinations in Europe, including Russia, Germany, and France, are also gaining traction.

Example: Osnabrück University in Germany offers information for incoming Chinese students on its website.

The increased variety of study destinations may be somewhat linked to a growing number of lower-income families seeking education abroad, as they will naturally seek different, more affordable options.

Changing policies may also play a role. For instance, the United States recently restricted F-1 visas for Chinese students studying in certain areas to one year (although they can apply to renew yearly), where they were previously allowed five years. The fields affected include high-growth sectors like robotics and technology, which could create huge opportunities for schools in other countries.

When considering possible future study destinations for Chinese students, it’s also important not to leave out one increasingly popular choice: China itself. As its economy has grown and its population has become more educated, the country has taken several steps to make its domestic study options more competitive.

The government has put considerable investment behind its so-called ‘C9’ universities- Tsinghua University, Peking University, Fudan University, Zhejiang University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Nanjing University, University of Science and Technology of China, Wuhan University, Sun Yat-Sen University, and Tongji University.

These leading institutions were part of China’s ‘World Class 2.0’ project launched in 2015, which aimed to propel all nine into the world’s top 15 universities by 2030. While they are not there yet, they have made some headway, with 6 of these institutions named in QS’s Global World University Rankings top 100 this year, the highest amount ever for the country.

Should this upward trend continue, staying home may become a more prestigious option for domestic students, while China may increase its popularity as an international study destination.

Example: The University of Science and Technology of China – one of the country’s C9 schools – posted this blog on the English version of its website about a welcome event for its international students. Top Chinese schools like this are expected to become increasingly active internationally.

More Chinese International Students are Returning Home After Graduation

Another major shift in Chinese students’ mindsets over the last few years relates to their ambitions after their studies. While having opportunities to remain in their destination country and work after graduation is still important to many, many Chinese international graduates are returning to their homeland after earning their qualifications.

The Chinese government reports that 544,500 international students returned to China in 2016, compared to just 186,200 in 2011—an increase of 132 percent. This is perhaps not surprising; the Chinese economy continues to grow and offer better income and opportunities for skilled workers, and, naturally, international students will see these advantages and look to use their global knowledge and expertise in this attractive marketplace.

Tellingly, one of the hottest sectors for returning graduates is applied sciences, including the tech sector. This area accounts for up to 15.5% of returnees according to a recent survey from the Centre for China and Globalization, although business-focused graduates were the highest in number:

This means schools might need to reconfigure student recruitment messaging for Chinese students. Once the focus has been on post-graduation visas or job possibilities, it may be necessary to research what your Chinese students’ qualifications can help them achieve in China. Focusing your recruitment efforts on growing sectors in China, like tech, may also prove fruitful.

Example: The University of Alberta highlights its research partnerships with Chinese universities and official bodies in energy, technology, and health on its websites.

In addition, it may become more important to be mindful of the challenges an international Chinese student will likely face upon returning home. While many overseas students find that their global perspectives, language skills, and prestigious education help them to secure work, the CCG survey also noted several areas in which they feel at a disadvantage, including unfamiliarity with the jobs market, a lack of a professional network, and even difficulty reintegrating with their own culture.

Offering students support and guidance in these areas and convincing them that the positives outweigh the negatives may be crucial to success. If you have a network of Chinese alumni graduates who will have access to or any students who have returned home and gotten prestigious positions, highlighting them may be beneficial.

Example: Central Washington University created a blog post about its first-ever event for alumni in China, which 130 graduates attended. Demonstrating that these networks exist for Chinese students could become increasingly important.

As much as the outlook and conditions in the country will continue to evolve, it is clear that investing in digital student recruitment in China will remain important for years to come. Being mindful of developments in the education sector and the digital world will help your school take advantage of new opportunities, adapt to challenges, and grow its presence in the Chinese market.

FAQ To Consider

What are the trends in education in China?

Social media marketing in China, at least in the wealthier regions, is now very much dominated by two sites: Sina Weibo and WeChat. The former is similar to Twitter, offering a microblogging platform that allows users to create short text posts, photos, and videos and follow others to keep track of the latest trends.